In 1936, nine American rowers took on the Nazis in front of Hitler and 75,000 screaming Germans. The story of the greatest Olympic race you’ve never heard of.

The 1936 U.S. Olympic rowing team from the University of Washington. From left: Don Hume, Joseph Rantz, George E. Hunt, James B. McMillin, John G. White, Gordon B. Adam, Charles Day, and Roger Morris. At center front is coxswain Robert G. Moch.

Photo courtesy of University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UW2234.

Sportswriter Grantland Rice called it the "high spot" of the 1936 Olympics. Bill Henry, who called the race for CBS, said it was "the outstanding victory of the Olympic Games." The event they’re describing wasn’t staged in Berlin’s Olympic Stadium, and it had nothing to do with Jesse Owens. It took place in the suburb of Grunau, when a group of college kids from the United States took on Germany and Italy in front of Hitler and 75,000 fans screaming for the Third Reich.

The results of the 1936 Olympic regatta were the inverse of that year’s track and field competition. On the track, American men won gold in the 100, 200, 400, and 800 meters; the 4-by-100 relay; both hurdles events; and the high jump, long jump, pole vault, and decathlon. (American women also won the 100 meters and the 4-by-100 relay.) German oarsmen, however, dominated on the water, capturing five gold medals and one silver in the six races preceding the eight-oared final. When a British pair finally beat a German shell, Henry and his CBS broadcast partner Cesar Saerchinger were relieved, according to Saerchinger’s book Hello, America!, as they’d “had to stand up for the German anthem and the ‘Horst Wessel’ song [the Nazi party anthem] after every event, until we were nauseated.”

A few minutes before 6 p.m. on Aug. 14, the final race was about to begin. The crowd, which included Hitler, Hermann Göring, and other Nazi officials, awaited another German victory.

INTERACTIVE: How badly would Usain Bolt destroy the best sprinter of 1896?

At the starting line, American coxswain Bob Moch looked anxiously into the face of Don Hume. Hume, the stroke of the crew, was tasked with setting the pace for the seven oarsmen rowing behind him. Yet something was very wrong. Hume's eyes remained closed for most of the warm-up, and his breathing seemed labored. Moch knew that Hume had been ill since the team arrived in Europe, but he had never seen his close friend look so listless before a big race. As the rest of the crew stirred nervously, trying to banish thoughts of the tremendous physical punishment awaiting them, Moch glanced at Hume and then across the water at the other eights. Big Jim McMillin, sitting in the five-seat, later remembered his thoughts at the starting line. "I had felt that if we rowed the best we knew how, we could get there," he told me in 2004, a year before his death at age 91. But, McMillin said, "everything went wrong from that point on."

INTERACTIVE: How badly would Usain Bolt destroy the best sprinter of 1896?

At the starting line, American coxswain Bob Moch looked anxiously into the face of Don Hume. Hume, the stroke of the crew, was tasked with setting the pace for the seven oarsmen rowing behind him. Yet something was very wrong. Hume's eyes remained closed for most of the warm-up, and his breathing seemed labored. Moch knew that Hume had been ill since the team arrived in Europe, but he had never seen his close friend look so listless before a big race. As the rest of the crew stirred nervously, trying to banish thoughts of the tremendous physical punishment awaiting them, Moch glanced at Hume and then across the water at the other eights. Big Jim McMillin, sitting in the five-seat, later remembered his thoughts at the starting line. "I had felt that if we rowed the best we knew how, we could get there," he told me in 2004, a year before his death at age 91. But, McMillin said, "everything went wrong from that point on."

The story of the 1936 Olympics remains focused on the brilliant achievements of Jesse Owens and the filmmaking of Leni Riefenstahl. But the Berlin Games were just as important for inaugurating the era of the modern Olympiad. This was the first Olympics that featured a torch relay from Mount Olympus, and the German Broadcasting Company installed the world's most technologically sophisticated television system to broadcast the games to theaters throughout Berlin. The Germans also constructed a massive shortwave broadcast center to ensure worldwide Olympics coverage.

Adolf Hitler opens the Olympic Games, Aug. 1, 1936.

Photo courtesy U.S. National Archives.

For the global radio audience, estimated at 300 million, the Olympics assumed a new prominence. Just four years earlier, the American radio networks (NBC and CBS) dropped live coverage of the games when the cash-strapped Los Angeles organizing committee demanded an exorbitant rights fee at the last minute. Because the Germans asked for no rights fees and offered their engineers and technical apparatus for free, Americans were able to listen to the games live for the first time.

On the morning of Aug. 14, many people in Seattle woke up excited to catch the regatta’s final event live on CBS. Those listeners had a vested interest in the race. The United States team, a crew from the University of Washington, came very close to missing the trip to Berlin. Immediately following the Huskies’ victory in the Olympic trials, the team was informed by the U.S. Olympic Committee that it needed to come up with $5,000 to pay its way to Berlin. Seeing an opening, Henry Penn Burke—chairman of the Olympic Rowing Committee and a University of Pennsylvania alum—offered to send his beloved Quakers in place of the Huskies. The sports editors of Seattle's top two newspapers, outraged on behalf of the local heroes, enlisted newsboys to solicit donations while hawking papers. With American Legion posts and Chambers of Commerce throughout the state chipping in, enough money was collected in three days to send the team to Berlin. As a consequence of the funding drive, remembered Gordon Adam, who rowed in the three-seat, "people in the city felt that they were stockholders in the operation."

MORE: How Olympians may reveal their nationality with just a smile.

MORE: How Olympians may reveal their nationality with just a smile.

The Washington crew had been rowing together for less than five months prior to the Olympics. Coach Al Ulbrickson had originally named a different group of rowers as the varsity at the start of the college season. The second boat, made up of strong but inexperienced oarsmen, knew they rowed faster than the first string and was angered by the slight. After the varsity shoved off the dock for their first practice, the angry eight carried their boat to the water silently. "We were standing about a little bit after we put the oars in the oarlock," Moch explained to me the year before he died. “Somebody said, 'You know this thing is going to fly.' "

The teammates soon devised a mantra. Quietly, they would repeat the letters L-G-B. When asked the meaning, they would explain it stood for "Let's get better." What it really meant was “Let’s go to Berlin.”

The Huskies’ first big triumph came in the Intercollegiate Rowing Association national championship in June. In that race, Washington successfully deployed its signature strategy. The Huskies always maintained a stroke rating below their opponents’, ignoring those moments when their competition opened up enormous leads. When all seemed lost, the coxswain Moch would call on Hume to raise the stroke rating. Employing near-perfect technique and synchronization, the boys would put their shell, the Husky Clipper, in a higher gear. At the IRA Championship, they sat in fifth place after the midway point, but blasted past the competition once the sprint began. It was a dominating, intimidating performance.

A few weeks later, the Huskies cruised past the competition in the Olympic trials. After surviving the funding scare, they crossed the Atlantic on the S.S. Manhattan with the rest of the American Olympic team. In today’s world, where Seattle and Berlin are separated by nine hours of jet flight, it is difficult to imagine how they felt to be travelling to Europe. McMillin told me the trip was "a dream”—like most of his teammates, he had never left the state of Washington before taking up rowing.

This photo, published in a German cigarette company's review of the Olympics, shows Robert Moch, George Hunt, John White, and Joe Rantz in Indian headdresses.

Courtesy Cigaretten—Bilderdienst Hamburg-Bahrenfeld GmbH.

Unlike its competition from the Ivy League, the Washington crew was composed of kids from working- and middle-class families. Rowing, then as now, was considered an elite sport. The 1924 Yale crew that won the gold medal in Paris, for instance, featured both a Rockefeller and Benjamin Spock (yes, Dr. Spock). But the Husky rowers could barely afford lunch, much less a trip to Berlin. Several paid their college tuition and living expenses from money earned through the National Youth Administration, a New Deal organization. "We used to sweep out the pavilion that was used for basketball and other events, we did the football field, we sold tickets, we ushered," McMillin remembered. His teammate Gordon Adam worked as a janitor’s assistant, washing windows and scrubbing floors for $15 a month.

Despite third-class accommodations, the crew enjoyed themselves on the passage to Europe. But Don Hume and John White caught colds on the boat, and others felt seasick. When the Manhattan arrived in Hamburg, the team was relieved to be back on land. But gray fog encased Berlin throughout the Olympics, with rain and an unseasonable cold spell chilling and dampening the massive Köpenick police barracks where the team was bunking. A particularly brutal qualifying race, in which the Huskies set the Olympic record while narrowly edging out a strong British eight, only exacerbated Hume's illness. He passed out at the finish line, only to revive when Moch splashed cold water on him. The victory, however, allowed the Huskies to rest while other boats fought through additional qualifying races.

MORE: America’s fat, English-hating, gold-medal-winning Olympic heroes of the early 20th century.

MORE: America’s fat, English-hating, gold-medal-winning Olympic heroes of the early 20th century.

On the morning of the final, Hume was in terrible shape. He shivered uncontrollably, and he appeared mentally and physically wan. With his eyes closed and his mouth slack, he barely pulled his oar during warm ups.

The race began in typical fashion for the Huskies. “We all know the Washington crew … is probably the slowest-starting crew in the world,” said CBS’ Bill Henry with a chuckle. “It gives everybody heart failure.” With the Americans “dragging along” in Henry’s words, the Italians and Germans were more than a boat length in front at the halfway mark of the 2000-meter race. McMillin, rowing in the middle of the eight, sensed something was amiss. "Somewhere about the middle of the race I knew we were not doing well and we were behind,” he told me. “I thought, God, we've come all this way from Seattle, and to end up our season like this ... it can't happen."

The German crew at the start line of the Olympic final.

Photo courtesy U.S. National Archives.

As the shells whizzed past, cameramen perched atop buoys captured the race for Germany’s top filmmaker, Leni Riefenstahl. German dominance on the water ensured that rowing events would feature prominently in Olympia, her classic propaganda film on the games. But the day of the rowing final was a disaster for Riefenstahl, as Olympic authorities, who were concerned about lightning, forced her to ground the balloon she’d set up to track the race from above. (When gas from the descending balloon escaped too quickly, cameraman Walter Frentz fell into the Spree River. He was not injured.) Riefenstahl ultimately interspersed her limited actual race footage with pre-recorded, dramatized film and audio. Every in-boat, water-level shot in the clip below was filmed before the final race, with fanciful audio mixed in. (Bob Moch did not call out “Push! Pull!” on every stroke.)

As the German crew powered toward the finish line, the crowd chanted “Deutsch-land! Deutsch-land!” in time with each stroke. The noise swelled, and the rowers sensed the finish line closing in. The Americans had to make their move. Moch, the coxswain, stared at Hume's face. With about 800 meters remaining his eyes opened and he began rowing with authority. Responding to Hume's emerging strength, the boat's stroke rating rose.

High above the grandstand at the finish line, CBS' Bill Henry watched the final sprint unfold:

It looks as though the United States [is] beginning to pour it on now! The Washington crew is driving hard on the outside of the course, they are coming very close now to getting into the lead! They have about 500 meters to go, perhaps a little less than 500 meters, and there is no question in the world that Washington has made up a tremendous amount of distance. … They have moved up definitely into third place. Italy is still leading, Germany is second, and Washington—the United States—has come up very rapidly on the outside. They are crowding up to the finish now with less than a quarter of a mile to go!

Click on the player below to listen to Henry’s call:

The resolve built from countless hours of practice kicked in. Within 300 meters, the Huskies pulled even with the tiring Germans and Italians. A supposed transcript of the German radio call, as published in a post-Olympic program, captures the excitement: “Still Italy! Then Germany! Now England! Ah, the Americans—their powerful spurts are irresistible! Their oars rip massively through the water!”

The crowd's roar became deafening as the three boats matched each other stroke for stroke. As they crossed the line together, the rowers couldn’t tell who had won. The men in all three boats recoiled or collapsed in exhaustion as the crowd quieted down to await the results. “Nobody said a word," Moch remembered.

After an interminable wait, the announcement came over the loudspeaker: USA 6:25.4, Italy 6:26.0, Germany 6:26.4. After almost six-and-a-half minutes of racing, just one second separated the three boats.

It would be the most physically demanding race any of them would ever row. "God, we were out of gas at the end," McMillin remembered. "How I struggled through that last 20 [strokes] I don't know."

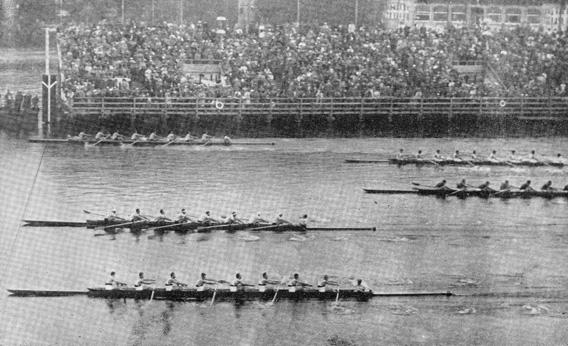

The American crew (top) crosses the finish line first.

Photo courtesy University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, UW1705.

After

regrouping, the Americans paddled their boat to the dock in front of the grandstand to receive the victors' laurel wreaths. In a separate ceremony in Berlin's Olympic stadium, Roger Morris, Charles Day, Gordon Adam, John White, James McMillin, George Hunt, Joe Rantz, Don Hume, and Robert Moch received their gold medals.* McMillin told me it was the most emotional moment of his life.

Hitler’s reaction to the U.S. victory was neither recorded by the assembled press nor described over the radio. “I didn’t give a damn about Hitler,” Bob Moch told me. “We didn’t care whether he existed or not. We were there to do a job.” The German radio broadcast reveled in the overall quality of the race, with the announcer boasting that Deutschland’s “bronze medal has a golden glow.” As the “Star-Spangled Banner” played, the crowd gave the Nazi salute to the American victors.

In the days after their victory, the American press swooned over the crew, with major articles appearing in all the dailies. The gold-medal performance still resonated the following spring, with Collier’sand the Saturday Evening Post paying Ulbrickson to describe the race. Seventy-five years later, though, the feats of the Washington crew have largely been forgotten. The first of the Huskies to cross the finish line, bowman Roger Morris, was the last to die. He passed away in 2009, and with him went the last participant memories of one of the greatest U.S. Olympic teams. Yet their legacy lives on in those still rowing on Seattle’s Montlake Cut. This June, Washington’s varsity men’s crew set a new course record in winning the Intercollegiate Rowing Association Championship. The men of the Husky Clipperwould have been proud.

Corrections, July 26, 2012: This article originally stated that rower Joseph Rantz had the nickname “Shorty.” That moniker belonged to his teammate George Hunt. (Return to the corrected sentence.) A photo caption originally misidentified one of the rowers in a photo of the U.S. Olympic team in Indian headdresses. The man pictured is George Hunt, not Gordon Adam.)